#ICEWomenWork

Women working as law enforcement officers at ICE fulfill the agency’s public safety and security mission with integrity and strength.

ICE prioritizes recruiting women candidates.

The ICE Women in Law Enforcement feature section provides useful information about career tracks at ICE, employment benefits, upcoming recruiting events, application requirements and an overview of the agency. Visit each month to learn how to become a law enforcement officer at ICE. Upcoming topics include DHS Hiring Fairs, Police Week, webinar schedules, new job postings, current and retired ICE law enforcement officers, women serving their communities, and women in the Department of Homeland Security. Follow #ICEWomenWork on Twitter to keep current on women in law enforcement.

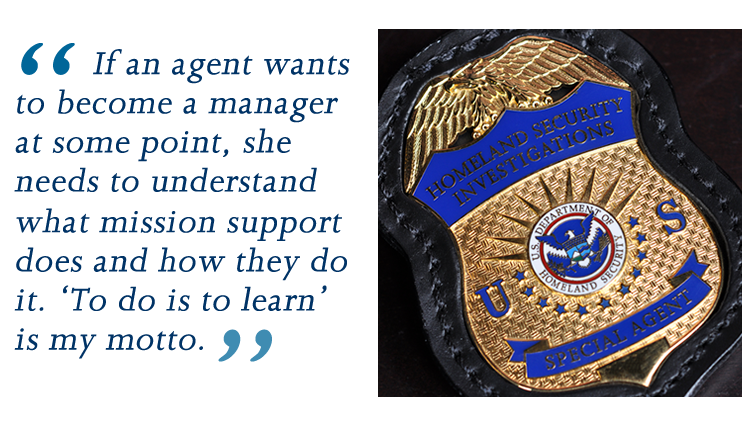

Professional career advice

ICE Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Special Agent Aegeda Fountaine offers practical words of career advice to aspiring law enforcement professionals. Special Agent Fountaine works with HSI in Houston, Texas. She is involved in a variety of criminal and civil investigations involving national security threats, terrorism, public safety, drug smuggling, child exploitation, human trafficking, financial crimes, and identity fraud. In addition, Special Agent Fountaine carries out the duties of a Certified Undercover Operation Program Manager. In this role, she ensures compliance and provides guidance on day-to-day operational and strategic decisions regarding undercover activities. She also coordinates activities with the Office of Investigations Headquarters, foreign offices and other agencies and reviews financial reports for proper use of funds. Special Agent Fountaine attended the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center as well as the HSI Undercover Manager’s, Operatives, and Fundamental Financial System Schools. She holds the Bachelor of Arts in Political Science from Southern University and A&M College, Baton Rouge, Louisiana.

Working with professional law enforcement women

ICE Homeland Security Investigations (HSI) Special Agent Allison Carter Anderson shares her experiences working with other female law enforcement professionals. She is assigned to the office of the Special Agent in Charge in Tampa, Florida. Focused on worksite enforcement investigations, she has also conducted narcotics and financial investigations. She is in training to become a coordinator for the ICE IMAGE (ICE Mutual Agreement between Government and Employers) program and also serves as a recruiter for her office in central and north Florida. Special Agent Carter Anderson began her career at Operation Alliance in San Ysidro, California where she investigated narcotics crimes and participated in several Title III wiretap investigations. She completed her special agent training at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in Brunswick, Georgia. Carrying on her family tradition of working for the federal government, she graduated from Florida State University in 2000 with a degree in History.

A day in the life of a female officer

ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) Deportation Officer Ayeisha Ramirez describes a typical work day in the New York City Field Office as part of the Fugitive Operations Unit. Previously, she worked in both the Non-Detained and Detained Units. Officer Ramirez began her law enforcement career in 2002 with legacy Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) as an Immigration Inspector at John F. Kennedy International Airport, and later as a Customs and Border Protection Officer performing duties in counter-terrorism response. In addition to her regular duties, Officer Ramirez serves as a Defensive Tactics Instructor and Special Emphasis Program Manager for ICE. She is a graduate of Wesleyan University, Middletown, Connecticut with a degree in International Relations and continues to donate time to her alma mater by participating in prospective student panels and alumni events.

Making the choice to work in law enforcement

ICE Enforcement and Removal Operations (ERO) leader Marisa A. Flores reveals why she chose the challenging field of law enforcement as a career. As ERO Acting Deputy Field Office Director, Los Angeles Field Office, Flores oversees and manages over 500 employees, 175 contract staff and an operating budget of $125 million. She previously held the position of Assistant Field Office Director in that office and managed the Criminal Alien Program, 287(g) Program, fugitive operations, detention and transportation operations, and detention management and compliance. After beginning her federal civil service with the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) as a mail and file clerk, Deputy Field Office Director Flores worked her way through the ranks as a student intern and deportation officer. She continued promotions as a detention and deportation officer and later as supervisory detention and deportation officer at ERO Headquarters in Washington, DC. She progressed to administrative management as Chief of Staff for the ERO Division of Policy and Communications and managed a budget of $21 million and a workforce of 112 employees. In 2010, she was promoted to Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations in support of the ERO Executive Associate and Deputy Executive Associate Directors, and assisted with the management of daily operations and procedures related to enforcement, detention and removal activity at headquarters and in the field. Marisa Flores is a graduate of the University of San Diego, where she majored in Spanish. She holds a Master of Forensic Sciences from National University.

ICE Trailblazers

ICE trailblazers Catherine W. Sanz, Rachel Cannon, Carol Libbey and Robyn Schmidt collectively possess the themes of the DHS Leadership Year that make exceptional leaders. They each earned the trailblazer title working in federal law enforcement at a time when few women had a presence in the field. Federal law enforcement employees today benefit from the work these individuals did, and continue to do, in breaking down barriers, destroying stereotypes and promoting equality for women, and all employees, at ICE and across the federal government.

Click below to read their stories:

- ICE leader Catherine W. Sanz: Promoting fairness in hiring, serving the ICE mission, establishing the ICE Office of Asset Forfeiture and challenging leadership rules

- ICE leader Rachel Cannon: Risking an unknown career, being the first woman to lead ICE Ft. Pierce, calling out truth and always recognizing the greater good

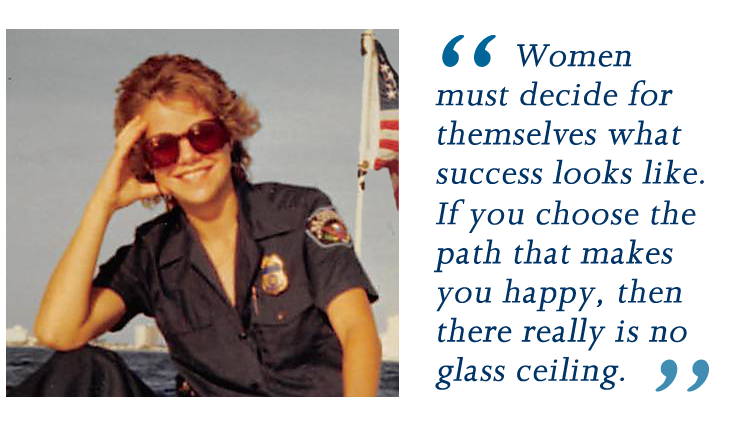

- ICE leader Carol Libbey: Focused on getting the job done, part of first U.S. Customs asset forfeiture group, instrumental in creating ICE seized property guidelines, deciding for herself what success looks like

- ICE leader Robyn Schmidt: Understanding the big picture, leading from every position held in her career, empowering colleagues through knowledge and learning her entire lifetime

- ICE leader Mary Loiselle: Started at the ground level, helping to stand-up ICE after the events of 9/11, advancing through plain hard work while respecting every colleague along the way

A Leader Developing Leaders: Catherine W. Sanz

Face-to-face, Special Agent Sanz looks you dead in the eye, thinks before she speaks, and chooses her words with economy. Imagining her interrogating a suspect brings out feelings of sympathy for the person on the opposite side of the table. She possesses a sense of humor, empathy and real-world problem-solving skills. All these traits served Catherine W. Sanz well in a career that began as Special Agent for the Drug Enforcement Administration, and finished as retired Assistant Director, Mission Support, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Office of Investigations.

Sanz vividly remembers what the man who hired her at the Federal Protective Service in Boston, Massachusetts, said to her when she started in 1977. It wasn’t to comment on her Criminal Justice degree from Northeastern University. He said, "You were hired because you look like you could take a punch."

Now, after succeeding in leadership positions at ICE, she believes things are better for women in law enforcement: "Back then, we fought to work the same as the men and be treated as equals to the men. Today, women are doing incredible and exciting things we never could have imagined."

After working as an agent for the U.S. Customs Service in Miami, Florida, Sanz supervised undercover child pornography and money laundering operations and investigations, general smuggling, and commercial fraud. Later, at U.S. Customs Service headquarters, she managed the agency’s asset forfeiture program which led to a detail as the Assistant Director for the Department of Treasury’s Executive Office of Asset Forfeiture.

In 2003, for newly formed ICE, she developed, implemented and ran the ICE Asset Forfeiture Program. Using her experience from field work and Treasury, Sanz facilitated the integration of customs functions into the brand-new U.S. Department of Homeland Security, ICE.

Currently, as Executive Director for the Women in Federal Law Enforcement (WIFLE) organization [i], Sanz works with federal employees, and others, to empower women in their federal law enforcement careers. “We want to create a network for women that takes them from the beginning to end of their careers, into retirement and second careers,” she said.

During her career as a leader at ICE, Sanz learned that female law enforcement professionals tend to retire at an earlier age than women in other professions, and the value of establishing critical professional networks for women to connect to each other. Sanz explains: “Women need to start sooner than the five years before retirement to figure out how they are going to live. They need to start in their forties figuring out if they want to work up to the mandatory retirement age of 57 and then work part-time, or leave when they are first eligible and go onto a full second career.”

Sanz often hears stories from women in law enforcement that highlight the sense of isolation women can experience on the job; “A young woman came up to me and broke into tears as she told me how isolated she felt from other women in her work.”

As ICE, and other federal law enforcement agencies, continue to hire more and more women, hopefully the individual sense of isolation will lessen. To move forward, we must look back.

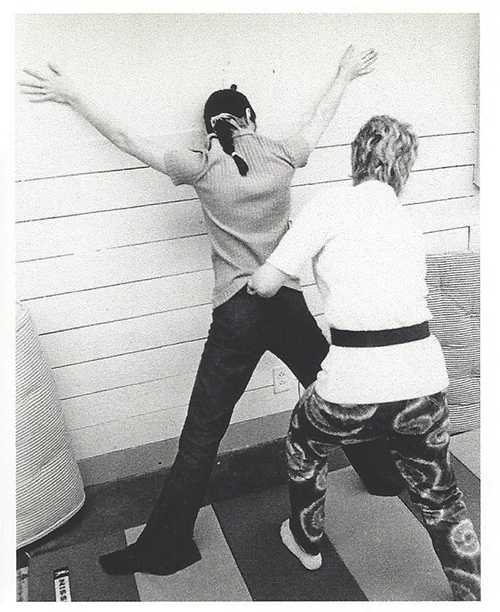

In professional law enforcement, historical bias was created by men. Sanz explains that as the field became more professional in the 1960s, artificial barriers in hiring were challenged by women, and men. [ii] For example, in some jurisdictions and states, a requirement existed that a police officer must be six feet tall. The height requirement inspired women, and men, to file lawsuits and a major 1971 Supreme Court decision eventually led to more fairness in law enforcement hiring. [iii] It was replaced with arbitrary training requirements, such as a 6-foot wall to be scaled, to discourage women and minority men from joining a force. It was not about finding recruits in the best physical shape to serve as police officers; it was about preventing women from joining law enforcement.

"There are still artificial barriers in hiring," said Sanz. Today, Sanz works to encourage ICE, and other federal agencies, to help increase understanding of artificial hiring requirements and to eliminate disconnects between hiring requirements and what agencies actually ask employees to do on the job. She also advises agencies on how women will self-select out of the hiring process altogether if messaging is biased toward men.

Despite the challenges, Sanz thinks women bring great qualities to the job: “Every woman should at least consider law enforcement as a career, because women are great at it. They have the superior skills of women: great collaboration, communication and empathy, and all those things that are intrinsic to law enforcement. In reality, very little time is spent on arrests, 85% of time is social work, analysis, coordination and administration.”

Sanz reflected on a career well-spent: “It’s the best career choice you can make; you will never have more fun than doing this job. You will never laugh harder and you will never have better friendships. In spite of my being in that first generation, and having to put up with a lot, it turned out to be the best thing I’ve ever done.”

i Disclaimer: The mention of any non-government organization does not constitute an ICE endorsement or sanction of the organization’s products, services, objectives or membership. | return to text

ii www.archives.gov | return to text

iii www.supremecourt.gov, Griggs v. Duke Power Co., decided March 8, 1971. | return to text

Engagement Culture Starts with Leadership: Rachel Cannon

The man asked her, “Have you ever thought about being an agent? I think you would be great.”

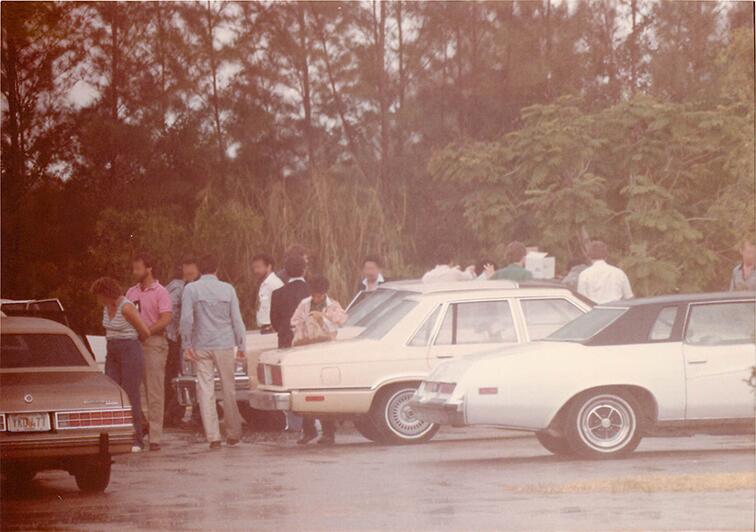

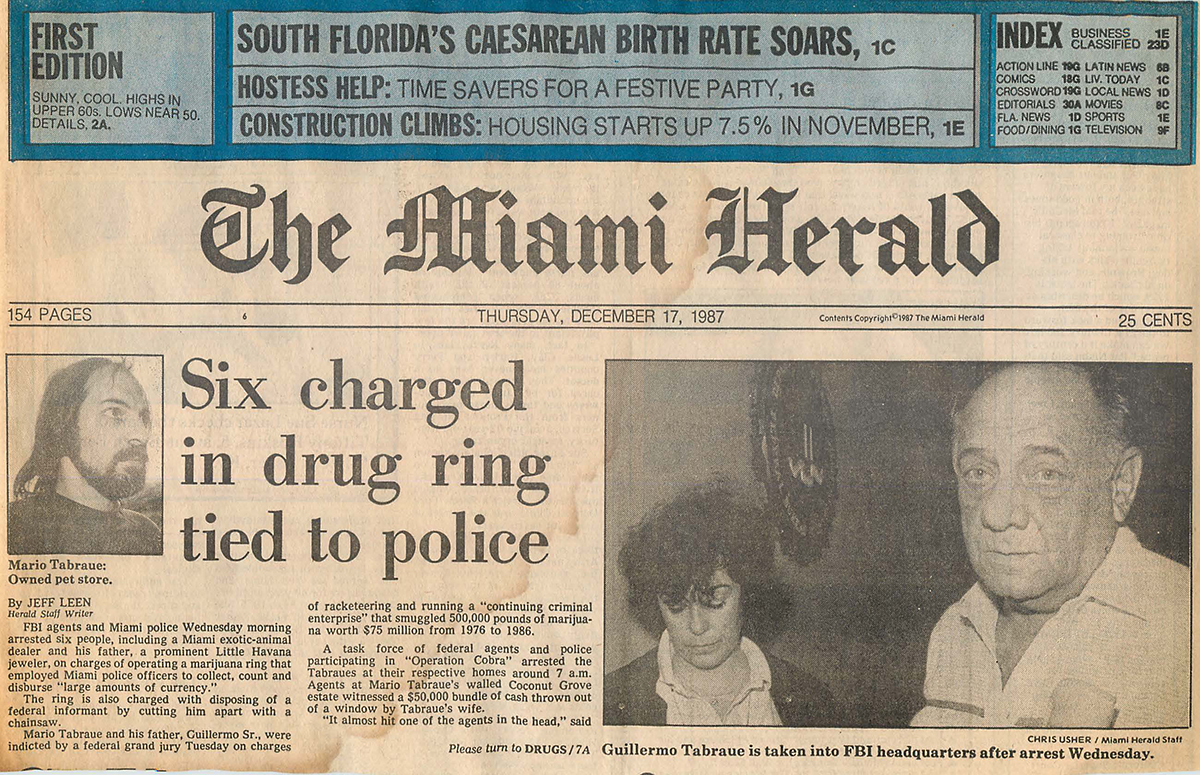

In 1979, Rachel Cannon was recruited while assisting federal agents serve a search warrant on an exotic bird importer in Miami suspected of smuggling endangered animals. At the time, she was working as a veterinary medical technician for the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Veterinary Services. By the end of that day, the agent who recognized something in Cannon used a typewriter to complete her application form and she became a Special Agent for the USDA, Office of the Inspector General.

Cannon never looked back.

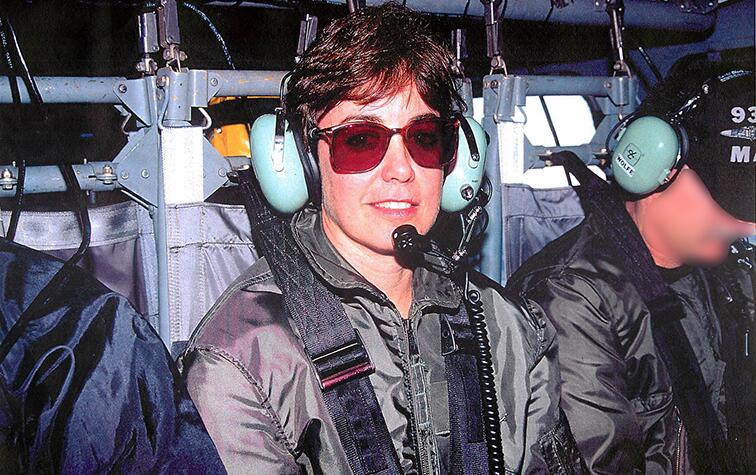

Her career next took her to the U.S. Department of the Treasury, U.S. Customs Service, Miami. The U.S. Customs Service later became part of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2003 when the U.S. Department of Homeland Security was established.

The mid-eighties were a busy time for the Miami regional office positioned at the mouth of the Miami river. Poised outside the back door of the office were “go-fast” boats the agents could jump in at a moment’s notice to chase down suspicious traffickers.

“I had the privilege of being in one of the largest female-managed offices the agency had (Miami),” said Cannon. “We had a female Special Agent in Charge, Catherine W. Sanz, and more female managers than any other office.”

Over the next 19 years, Cannon worked as Special Agent and Supervisory Special Agent for the Asset Identification and Removal Group. Her leadership positions in Miami included Assistant Special Agent in Charge, Office of Investigations, and Coordinator of the Florida/Caribbean Regional Organized Crime Drug Enforcement Task Force. In the national capitol region, she worked as Special Agent in the Washington Field Office, Reston, Virginia, and Supervisory Program Manager of the National Financial Enforcement Program, Washington, D.C.

One of the few women to work as an agent in federal law enforcement in the 1970s and 1980s, Cannon recognizes that women are still the minority and that gender disparity creates undeniable challenges. “The bottom line is, traditionally, law enforcement has been a man’s job,” she said. “Women have to complete a facsimile of paramilitary training and then enter a bullpen atmosphere; they need to be able to assimilate into that culture while being capable of shutting down bad and offensive behavior, immediately, before it escalates or becomes normalized.”

She has her own philosophy when dealing with gender issues in law enforcement: “I am not a female or male – I’m an agent who was hired to do a job and that’s what I do.”

After U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) stood up, Cannon reached a milestone in her career and for women in federal law enforcement. In 2004, she became the first female Resident Agent in Charge of the Fort Pierce, Florida, field office, a border protection post. ICE made a good decision putting Cannon in charge and she also had the support of her predecessor, Alan Westerman. “I think she’s got the background and experience for the job up here and she’s going to do a fine job,” he said.[i]

After many years of service and now retired from ICE, Cannon oversees the Association of Customs and HSI Special Agents (ACHSIA) as Executive Director.

Cannon believes federal law enforcement for women has changed for the better and provides a more conducive environment than it did when she started out in the mid-eighties, but questions the sacrifices women made for acceptance: “When I got the call, I was there, period. My go-bag was always packed and ready to go. Now there exists a worklife balance, but back then, female, and male, agents coming up were told, ‘if we wanted you to have a personal life, we would have issued it to you.’ That is what the majority of us lived by – to the detriment of our relationships and families.

I never thought of myself as a woman; I always thought of myself as an agent.”

Despite those challenging times, Cannon’s early career was fun and satisfying. “Everyone worked hard, but played hard too. Things were on a smaller scale, and you had a very tight esprit d’corps.”

She encourages women at ICE, other federal agencies, and in state and local law enforcement to use their valuable skills and realize it is acceptable to show sensitivity and compassion on the job. Most importantly, women cannot allow anyone to prevent them from achieving their goals.

She believes that the job of federal law enforcement is about working as a team to protect the people and commerce of the U.S. while putting criminals in jail.

“Everything works much better when people work together rather than for themselves. Women can lead investigations away from people seeking individual glory and toward team work and the greater good. It’s about working together so everyone can share the success.”

i The News, St. Lucie County, “There’s a new federal agent in town,” August 8, 2004. | return to text

Serving People, Serves Mission: Carol Libbey

"What do we do with her?"

The male supervisor assigned to Carol Libbey in the mid-1980s asked the question. Across the room, his colleague looked at Libbey and stated, "I need a cup of coffee." Libbey replied, "there's the pot," and began her career as one of the first female federal law enforcement officers in Ft. Lauderdale, Florida.

Carol Libbey embodies many women at U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and other federal agencies: employees who do great work while serving their missions and the American people.

Libbey benefitted from a cooperative education - alternating school and paid field work every semester - in criminal justice at Northeastern University. She was hired as a co-op student with the U.S. Customs Service, then part of the U.S. Department of Treasury Department, and the experience led to a full-time position as Customs Investigator.

At U.S. Customs in 1985, Libbey, and other officers, patrolled the water around Ft. Lauderdale looking for boats approaching land from foreign destinations; boats approaching from outside a three-mile radius were automatically considered foreign. The small boats would sometimes travel out to a larger vessel and offload cargo to bring into shore. Often, U.S. Customs partnered with state and local law enforcement agencies.

Libbey's typical shift could be a week of days or nights. The intensity, pace, and stress of it was relentless. While working as a female officer with mostly male colleagues and unwinding ropes to take the boats out from the dock, Libbey remembers hearing one of her colleagues stating, "women shouldn't be in law enforcement." Unfortunately, the comment was made right before they were departing for their shift.

Officer Libbey chose pragmatism as a response, "Fine, but get the lines ready; it's time to go out."

She did her job.

"You're not going to change their minds," she said, "so there is no point starting an argument. You go do your job. You do it to the best of your ability."

She made her reputation on the outstanding quality of her work. On one of her patrols, the officers investigated a 25-foot outboard vessel. Her colleagues were ready to clear it but Libbey could not take her eyes off two white leather pillar seats. “They said they were fishing, but I don’t see any fishing equipment,” she said. “Let’s remove these seats and take a look.”

After removing the seats, the officers peered beneath the deck and found hundreds of pounds of marijuana, wrapped and lining the entire fiberglass hull of the vessel. Libbey heard fewer comments from her colleagues after that.

While in Ft. Lauderdale, Libbey shared her experience with the younger generation. She led the U.S. Customs supported Explorers; a program in which agency representatives met with youth of the community and conducted a program that developed character, leadership, citizenship and life skills through basic law enforcement training.

Libbey moved to Miami in 1989 and became part of the interagency Florida Joint Task Group started by President George H.W. Bush. Libbey worked in conjunction with Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) agents as part of the initiative. U.S. Customs and DEA agents worked in teams, at places like the Miami International Airport, conducted surveillance on people and cargo, searched for drugs and made arrests. Some weeks, Libbey made up to 25 individual arrests.

While working at U.S. Customs, Libbey was on the forefront of creating policy and establishing guidelines for working with seized property and confidential informants and for undercover operations. During a reorganization of U.S. Customs, the Miami office formed a group of agents to write new guidelines, in which Libbey was instrumental. Many of ICE's current guidelines are based on what was developed by U.S. Customs.

She later joined the Miami Investigative Drug Asset Seizure Group in Miami, known as "MIDAS," the first U.S. Customs asset forfeiture group in the nation which focused on seizing goods bought with proceeds from illegal crimes. MIDAS developed as a method to deter repeat offenders; defendants were willing to go to prison rather than forfeit their goods to the government. Once released, they would begin their illegal activities again, using their assets. Asset forfeiture puts the focus on seizing all goods at the of time illegal activity so there are no assets to use in future crimes.

MIDAS seized houses, boats, money and anything of value, including a Salvador Dalí painting and a moon rock. Libbey lent her expertise to a six-month detail in Las Vegas to assist with a multimillion dollar fraud and money laundering investigation. A Japanese citizen sold hundreds of memberships to a non-existent golf course and brought the proceeds to the United States. What monies he did not gamble away, he used to purchase two golf courses, a hotel, multiple houses in several states, cars and jewelry. Everything was seized and forfeited to the Treasury Forfeiture Fund.

One of the largest cases Libbey worked in Miami was with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Internal Revenue Service. The subject was buying and selling illegal Freon, and hiding all his holdings in different shell corporations. He was arrested and his proceeds, including a bottling plant, were seized in the largest asset forfeiture case for EPA violations at the time. Libbey, with the other cases agents, received the EPA National Stratospheric Ozone Protection Award that year for their work on the case.

As a program manager in the earliest days of ICE, Libbey led all ICE Asset Investigative Removal Groups nationwide. In addition, she shared her expertise by helping to create asset forfeiture curriculum and teaching courses.

As part of her duties at ICE, during the Department of Homeland Security's first years, Libbey acted as ICE liaison to the DHS Assistant Secretary for Border and Transportation Security. Her expertise on customs' issues assisted DHS in coordinating functions with other agencies, many of which were not familiar with the U.S. Customs-ICE mission.

Now retired, her final years at ICE were spent with the Office of Professional Responsibility, Professional Investigations Unit.

Libbey served the mission of ICE by acting in supervisory positions whenever the opportunity arose. She advises others to find mentors and opportunities where they can; "If you're in a smaller office, seek out a female mentor in a larger office or try a detail. Remember you don't always have to reach out to a female; you can also reach out to a male friend or mentor. Joining a professional organization, like Women in Federal Law Enforcement (WIFLE)[i] can be a good way to meet people, get involved and find mentors."

Working as a volunteer for the Association of Customs and HSI Special Agents (ACHSIA)[ii], Libbey works to connect older members to younger ones to share hard-earned wisdom.

After a full career in federal law enforcement, public service and volunteer work, Libbey imparts the following advice to women aspiring to law enforcement careers; "Women must decide for themselves what success looks like. If you choose the path that makes you happy, then there really is no glass ceiling."

i, ii Disclaimer: The mention of any non-government organization does not constitute an ICE endorsement or sanction of the organization’s products, services, objectives or membership. | return to text

Lead From Where You Are: Robyn Schmidt

"Leadership Year will be our chance to reinforce a culture of leadership excellence throughout the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and highlight the importance of leadership at all levels." With these words, DHS Leadership Year launched in October 2017.

Senior DHS leadership spent the previous months visiting DHS employees across the country, recognized leadership exhibited at every level of employment and felt inspired to develop an initiative to encourage and cultivate that leadership.

U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) boasts a legacy of strong leaders from each of the agencies that came together under the Homeland Security Act of 2002 to form ICE.

In 1983, retired ICE Management Program Analyst Robyn Schmidt already epitomized one of the Leadership Year's themes: Lead From Where You Are. Working for the U.S. Customs Service in Miami, Florida, she reported to the Assistant Regional Commissioner for Enforcement.

Schmidt did not have a narrowly defined list of duties. In the early days of her tenure, she managed a very busy office and handled all administrative work in support of enforcement operations. "At that time," Schmidt said, "every special-agent-in-charge office within the southeast region reported to our office for all their investigative and administrative needs."

Using a pragmatic approach, Schmidt maintained good working relationships with all the agents she worked with; "I was the only woman in that office and I let them know I was the boss and that was how things had to be; they knew they needed me. Things were the same for everyone." She was engaged and integrated into the agents' work by being involved in every aspect of each process.

"The job gave me a broad picture of what U.S. Customs did," she said. "Every morning, I read the reports of investigation the agents from all offices generated and learned what they were doing out on the streets. I was able to put the pieces of the puzzle together." The fact that she was at work by 6:30 a.m. gave her an early start on the day. Schmidt noticed an increase in the number of female employees, "As the years passed, several other women did come to our office in various positions."

The Regional Commissioner Offices were dismantled in 1991 and the structure of the Office of Investigations changed; Schmidt transitioned to Logistics Management for the Special Agent in Charge, Miami office.

Once ICE stood up in 2003, Schmidt managed over 400 government vehicles, the associated communications equipment, resulting evidence and the closed case file room as a Logistics Team Leader.

It was during this time, she started to notice more women leading at ICE. "They started recruiting more women at Miami and group supervisors were women," Schmidt said. "This was when I worked under my first female Assistant Agent in Charge for Administration, Rachel Cannon. Women were coming in and wanting to lead. I remember in the early days, when women came in, even as agents, it was expected that they would do the de facto administrative work. You would hear, 'You're supposed to make the coffee because you're the girl.'

"Well, I don't make the coffee."

Schmidt rounded out her career working in the ICE Homeland Security Investigations Technical Operations Unit in Lorton, Virginia - "I worked under my first woman Unit Chief at the end of my career and she was an outstanding person and leader."

Schmidt encourages new ICE agents and officers to experience law enforcement from the administrative side as part of their training. "If an agent wants to become a manager at some point, she needs to understand what mission support does and how they do it," she said. "In Miami, when the Academy sent new agents for training, we encouraged the special agent in charge to have them rotate through the mission support areas. I would have them in the closed case file room and evidence room to learn the big picture. 'To do is to learn' is my motto."

Her advice to ICE employees in mission support and agents is the same; "Keep an open mind and don't judge people when you first meet them; let them show themselves to you. Keep a positive attitude about the job and be willing to learn."

ICE leader started at ground level and rose to top: Mary Loiselle

Some federal employees gain experience from leadership roles at multiple government agencies. Others choose to work a combination of private sector, military and civilian government service jobs. Mary Loiselle focused on immigration work and never wavered. She retired from U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2010 with 32 years invested in the fair enforcement of the country’s immigration laws.

Loiselle began her career as an immigration inspector with legacy U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in Niagara Falls, New York. She completed basic training at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center in 1979, and met her future husband.

“I did not come up through the law enforcement position route. At the time, ‘inspections’ wasn’t considered law enforcement, nor was it a law enforcement ‘covered’ position,” she said.

Her skills were quickly recognized by leadership and rewarded with promotions, but Loiselle already realized her future would benefit from a comprehensive understanding of immigration issues. Over the next few years, she worked in the examinations section with legacy INS as an examiner, adjudicating applications for permanent residents, children adopted by U.S. citizens abroad and naturalization.

The events of 9/11 galvanized the government to unify national homeland security efforts with the merging of 22 separate government departments and agencies. Standing up the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in 2003 transformed the federal government, and with it, many individual lives. Loiselle remembers the time; “Being involved with building an agency from the ground up was very exciting. I never thought I would leave western New York. I came down to headquarters for a detail, after DHS was formed, for six months. I got my name known and was hired as a field office director.”

Loiselle remembers the first time she saw Julie Myers, at the time, the incoming assistant secretary of ICE. She was working on then DHS Michael Chertoff’s Secure Border Initiative in the summer and fall of 2005; “This young woman came in looking around and I thought, ‘oh my gosh she’s so young.’ Someone said, ‘that’s Julie Myers, she’s going to be the head of ICE.’ I loved working for her, she was eager to learn, she got a lot of people involved, and she was decisive.”

Loiselle now recognizes it was during this challenging time of change that she and her team, under the leadership of DHS Secretary Michael Chertoff and Julie Myers, were able to accomplish the most important work of their careers.

“When I first came in as the Field Office Director for the Washington Field Office, there was a huge caseload, and everyone was overworked and short-staffed. There was no deputy, no assistant field office directors or middle management personnel. We started hiring and growing, opening offices in Richmond, Roanoke, Norfolk and Harrisonburg. John Torres came in as the head of Detention and Removal Operations and was there for most of the expansion.”

Under Field Office Director Loiselle’s leadership, the Washington Field Office team implemented layers of management and support staffing and hired employees to execute an increased work load directly proportional to the new DHS. During her three-year tenure, the number of staff in that office tripled, alien removals increased by eleven percent while nationwide removals declined, new fugitive operations and criminal alien programs were established, and the Washington Field Office became one of the hubs for large charter removal flights.

Like many in leadership positions, Loiselle found her way to advancement by following her interests and instincts. She volunteered for a detail to assist with recovery from Hurricane Katrina in 2005 and became known to the wider ICE and DHS communities. She eventually earned a Senior Executive Service (SES) position through hard work, field work and executive experience.

Loiselle was appointed ICE deputy assistant director for detention management in 2007, one of a series of management jobs she held at headquarters over the next few years that culminated with her service as deputy director for Detention and Removal Operations in 2008. As deputy director, she oversaw 24 field offices and a $2.8 billion budget.

As a woman in leadership positions in the predominantly male law enforcement profession, Loiselle often felt like a minority in meetings and at conferences. “Earlier in my field office director career, I remember going to conferences and only four or five people, out of 24 attendees, were women,” she said.

“Sitting in some meetings,” she said, “I would look around and think ‘I am the only woman in here.’

“Sometimes you have to make a point of speaking up as a woman. Having said that, I rarely, if ever, felt my opinion was not respected.”

Loiselle advises ICE employees interested in advancement to learn as much as possible about other positions at the agency, to volunteer for details to learn what goes on in other offices and to be as flexible as possible. “Great leaders listen and have open minds,” she says, “you don’t have to know everything as a boss, but you have to know who to go to for the answer.”

Like other retired ICE employees, Loiselle stays active through the ICE Foundation and makes a point to keep current with news about ICE. “The people of ICE continue to do their jobs, no matter what headlines say, without getting enough respect,” she said. “You have my utmost respect.”

Learn more about how ERO Deportation Office Yomarel Justiniano does her job every day, HSI Special Agent Ellen Pierson paid tribute to officers killed in the line of duty, and how ICE recognizes Women’s History Month.

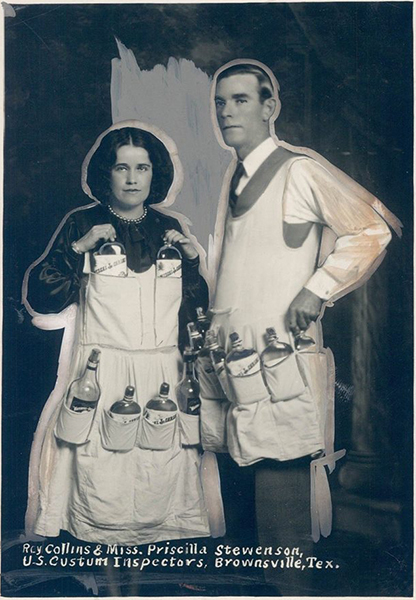

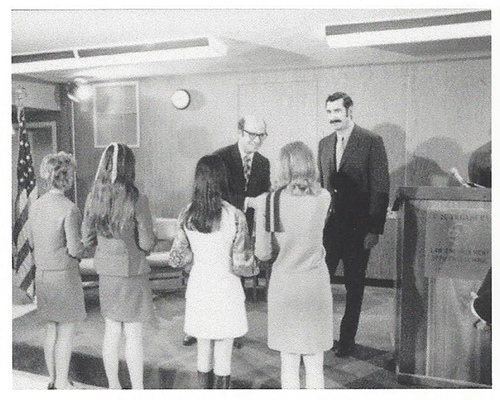

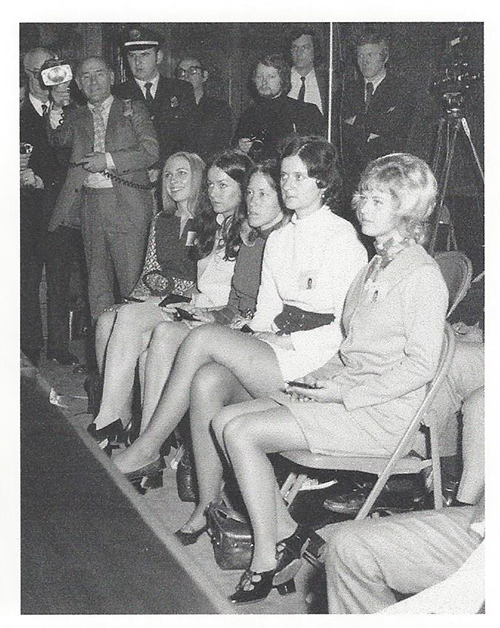

5 Historical Facts about Women at ICE

* Information provided by U.S. Customs and Border Protection historians